This article on MSNBC came across my radar recently. It’s called “This Week in God, 10.4.14” which, without spending too much time, suggests that it is a weekly thing. Reading it over didn’t make me really want to dig too deep to see if that’s true, in part because I don’t think I will ever understand how anti-theism could bring anyone joy other than the satisfaction of tearing someone else down. And it also spouted some of the same claptrap that proves, time and again, that if you say something mangled enough times people will think it’s true.

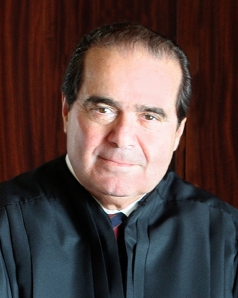

I will say, though, kudos to Antonin Scalia for always sending the other half of the political spectrum into a tizzy. It always cracks me up to see it happen, as they also turn a blind eye to Justice Ginsberg for virtually the same thing that they accuse Scalia of doing: politicizing the bench. The difference is that they agree with Ginsberg. However, that’s neither here nor there, because the real crux of the article is that religion is out to get you and Scalia is hell-bent on tearing down that grand old Constitutional wall of separation between church and state.

A.) THE INVISIBLE WALL

For those with a short memory, not that long ago a Senate candidate was the subject of much derision for questioning where the “separation of church and state” is in the Constitution. Christine O’Donnell was roundly ridiculed (and actually laughed at) when she questioned “Where in the Constitution is separation of church and state?” during a debate. That is how ingrained the notion is today, to the point where a person is considered a fool for “not knowing” that the First Amendment is, in part, about separating church and state.

The trouble is, the phrase “wall of separation between church and state” is actually nowhere in the Constitution, so the question is legitimate. The first article quotes the Constitution as being a “secular document, which separates religion and government”, so it should be pretty evident from reading the Constitution that there is a big wall somewhere. The only two places religion is mentioned in the Constitution are Article VI, Section 3, which states:

“The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

And the First Amendment to the Constitution, which states:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

One will notice that, quite literally, the phrase “wall of separation between church and state” appears nowhere in the Constitution. So where did it come from?

B.) WALLS TAKE TIME

To understand where the phrase came from and how it entered our legal lexicon, it requires a bit of history and a timeline:

1776 – The United States gains its independence.

1788 – The Constitution is ratified.

1791 – Bill of Rights enacted, which included the First Amendment.

1802 – Thomas Jefferson reflects on the First Amendment in a letter to the Danbury Church, first using the phrase “wall of separation between church and state.”

1868 – The Fourteenth Amendment is passed, incorporating the Bill of Rights (including the First Amendment) into State law. Previously, all portions of the Constitution only applied to the Federal Government.

1878 – Reynolds vs. U.S., which is the first case of First Amendment jurisprudence that uses Jefferson’s “wall of separation between church and state.”

1947 – Everson vs. Board of Education, which is the first case to apply the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to a State law under the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause.

So, there is nearly a 100 year gap between the writing of the Constitution and the first incorporation of the notion of “wall of separation between church and state” in the legal history of the United States, and that entry was via judicial opinion and not some founding document or amendment. An interpretation is not the same thing as the statement being interpreted.

Still, none of that means it’s necessarily wrong. Thomas Jefferson was one of our founding fathers, and his opinion on the First Amendment should hold sway, particularly for a self-proclaimed originalist like Scalia. So what’s the deal?

C.) ESTABLISHMENT OF RELIGION

First, you have to look at the First Amendment itself, which prohibits laws respecting the establishment of religion. What one needs to understand is that, at the time of the writing of the Constitution, there were in fact “official” churches in the various colonies. Many of them retained the Church of England as established churches, whereas others (like Connecticut and Massachusetts) had established Congregational denominations. Some of them were not disestablished until well into the 1800’s (on its own or because the First Amendment did not apply to the States until the Fourteenth Amendment’s passage). There were, of course, people who opposed disestablishment. They were called antidisestablishmentarianists, and I’m only pointing that out because come on, how often do you get to say antidisestablishmentarianists?

Furthermore, James Madison’s initial proposed language was to prohibit the establishment of a “national religion.” This was opposed by the Anti-Federalists, who strongly disagreed with the creation of a stronger, central federal government under the notion that hey, didn’t we just fight a war to get away from a strong national government? The word “national” was quite contentious for those who want a federal state where the individual member states retained a great deal of sovereignty, but it showed a key point. The Establishment Clause was really about not having an official state-sponsored church or religion.

D.) WHAT IS A WALL, ANYWAY?

So, coming from a position that the First Amendment was trying to avoid the Church of the United States, we come to Thomas Jefferson’s phrase in the letter to the Danbury Church. But before we dive into that, let’s think about something that seems readily apparent and is often glossed over: what exactly is a wall?

A wall, by definition in this context, is a brick or stone structure that separates one area from another. So, wall of separation is kind of redundant. But that’s beside the point. The point is, one person builds a wall to keep crap from one side from getting into the other. The Great Wall of China is a great example. The Chinese built it to keep people like the Mongols the heck away from them. So, the “wall of separation” begs the question: WHO built it, and WHO were they attempting to keep out? I doubt you’ll find many cases where two parties set aside their mutual hatred to build a wall together, shake hands when they finished, and then flicked each other off as they went back to their own side. Or times when someone built a wall to protect someone else from the dangers of the people building the wall.

We already know the parties in this one: church (religion) and state. So, did people build the wall to protect state from the church, or did people build the wall to protect the church from the state? Oddly enough, Jefferson answers this question in his letter to the Danbury Church, a minority Protestant denomination afraid that their rights to religious freedom were in danger:

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his god, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their “legislature” should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.”

Jefferson, in keeping with his general opinions that government = eventual tyranny, wanted to protect religion, a right of conscience and a natural right, from the powers of government in his above reassuring statement. The wall is there to protect the right of conscience, that natural right to religion that is between a man and his god. In fact, that was the whole purpose of the Bill of Rights, which Jefferson supported:

“A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.”

The founding fathers had a unique opportunity in front of them: after fighting the tyranny of government, and needing to build a new one out of necessity, they stood as free men with the ability to build a cage for the monster before the monster was even born. A monster that they knew would inevitably rear its ugly head, even if it were a necessary evil. So, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution as a whole, is meant to protect the rights of the people from government. The whole thing is a cage built of walls of separation between the rights of man and the state, built by free men as a necessary protection of their liberty.

E.) SHIFT IN POLARITY

Somewhere along the line, though, the whole wall got turned on its head. Somehow, we now think as if the Great Wall of China was built by the Chinese to protect the ways of the nomadic tribes to the north. In Reynolds vs. U.S., the wall of separation phrase was first used in a judicial decision, and it focused on a different portion of Jefferson’s statement: namely that the powers of government reach actions and not opinions. So, it was ruled that an anti-bigamy law could stand against a Mormon claim that it violated the free exercise of his religion. There is certainly truth to that argument that government could restrict action, but the question arose as to whether the action by the United States trampled the free exercise of the religion of Reynolds. So, it was centered on whether or not the state breached the wall protecting the right to free exercise, again showing the distinction about who the wall is there to ultimately protect.

The focus on action is certainly a legitimate one. The argument was made by the court that allowing any action under the auspices of religion could eventually lead to someone making the argument that human sacrifice was a-ok because it was a religious practice. The distinction here, though, is that the action being discussed is between citizens. The rights an individual has as it pertains to other human beings is not the same as the rights a person has in relation to the government. So, the first citing of the wall had little to do with the notion of keeping religion out of government, but rather if government overstepped its bounds.

Everson vs. Board of Education (again, a case from 1947) was really the decision that truly defined the modern view of the wall and that it applied to both the Federal Government and the States. The language and tone in the majority opinion, which ruled that reimbursement for transportation to private schools was allowable even though a large percentage of those private schools were parochial, stands in pretty stark contrast to the language cited thus far:

“The ‘establishment of religion’ clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between Church and State.”

The first sentence is the exact meaning of the Establishment Clause: no state church. However, it then starts down the trail of aiding any or all religions, forcing people to go to or stay away from church, profess a belief, etc. This was really the turning point, because it shifted the focus of any and all state action to the Establishment Clause, i.e. any action is de facto establishing a state church. Which seems silly in the context of transportation reimbursement somehow converting the State of New Jersey into a Catholic state deferring to the Vatican.

So is it ok for the government to force someone to go to church? Of course it isn’t, but I truly think the court came to the right decision for the wrong reason, and we’ve been spiraling ever since. Every single one of the things cited by Justice Black in the above statement, after the first sentence, deal with the violation of the right to free exercise of religion by an individual, NOT the establishment of a state church. Can the state pass a law which aids one religion? Probably not, because it probably violates the free exercise rights of others who aren’t getting that aid, not because it makes an official state church. Can the government force someone to go to church? No, because that violates their free exercise rights under the First Amendment, not because it establishes a state church.

It may seem like a distinction without a difference, but it truly isn’t. On the one hand, from a free exercise perspective, the focus is on individual rights and protecting them. On the other hand, you are declaring that the wall of separation was built to protect the state from religion. It changed from protecting religious freedom, to a declaration of complete neutrality and, quite frankly, antipathy towards religion. Combining everything under the Establishment Clause has led to the current conundrum, because it has now bled even further from simply prohibiting passing laws to virtually any action by any member in public office. We can no longer balance free exercise of religion with keeping it away from the public sphere because they now clash. They wouldn’t clash, however, if the view of the wall didn’t shift.

F.) WHERE WE STAND NOW

The notion of this wall keeping religion out of the state, instead of keeping the state out of the conscience of free men, is beginning to even further decay to the point where we are now seeing the exact opposite of the original intent. Our current President has referred to religious freedom again and again as the “freedom of worship.” This may seem like no big deal, but in actuality it is the next step in thinking after the polarity switch (whether knowingly or not). The insinuation is that you are free to worship, and you worship at your place of worship. It is an entirely private matter behind closed doors and away from the public sphere. So, we have now gone from protecting the religious rights of individuals from the state by walling off the state, to protecting the state from the religious rights or people, to an even further point where we are building the walls around religion to entirely hem them in.

The whole modern notion of a complete removal of any religion from the public sphere has led to a sort of absurdity in this regard. If I was a Lutheran, and I was deeply religious, what am I supposed to do if I get to become an elected official? How does one check his entire moral worldview at the door when taking public office, which in large part deals with moral dilemmas on a daily basis? Is using my Lutheran principles to guide my decisions in passing legislation, no matter how it is backed by Constitutional authority, a violation of the Establishment Clause? However, that’s where we are. We certainly haven’t legislatively disallowed any religious views for an elected official, but in practice we are acting that way when we have converted the freedom of religion into the freedom of private worship. It was never intended that a public official should check their religion at the door.

You’ll notice something that wasn’t discussed: atheism. In actuality, atheism is an absence of something, namely an absence of a belief in any deities. By its very nature, you cannot exercise a non-belief because they are mutually exclusive activities. Belief requires some actual thing to be believed, and atheism at its core declares there isn’t a thing to be believed in. So, where does that stand in terms of the First Amendment? How has the right to be free from religion somehow weaved its way into the free exercise of religion? How is religion-neutral, which is essentially no religion at all, the new standard? This is in stark contrast, again, to the original intention of the founding fathers, which was to protect the religious rights of the people, but it is a natural end to the hemming in of religion we see today.

So here we stand. The state must be protected from religion, and we are slowly getting to the point where we are declaring the natural state of the public is religion-neutral. Which, is quite honestly, a large difference from where we started. For those who aren’t religious, this is no big deal. However, one should probably step back and marvel at how a right, in the Bill of Rights, has morphed so much even though a single written word of it has never changed. Don’t think for a second that this can’t happen in the future to other rights: all it takes is one court decision, with a couple of justices who think about something differently than you, to some day declare that 2+2=5 and make it the law of the land.

I guess I need to circle back to the beginning after such a long rant. Was Scalia wrong? I guess opinions can differ, but I think it’s safe to say a morphing Constitution, for better or worse, is a modern reality, when you can take one thing and make it mean something completely different over time. Not to mention convince an entire public that a phrase exists in the Constitution when in actuality it can’t be found anywhere in the document. Or convince an entire public that they should be thankful that that wall is there to protect the wolves from the sheep.