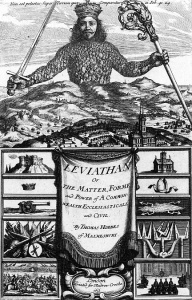

I hesitated for a long time typing out my thoughts on the recent marriage debates after the Supreme Court issued its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. The topic is such an emotionally charged one, with such polarizing opinions, that to take a stance or have an opinion necessitates a reality whereupon you will find yourself in a trench with bullets flying in your general direction. It was viewing the debate as such, reminiscent of World War I trench warfare, that made me change my mind in discussing the matter. World War I is an analogy that is apt because it makes a person take defined sides and, even though it implies a person will be fired upon, it also assumes that they will be firing back. I, however, plan on taking the madman’s course by waltzing between the trenches.

I sincerely believe we all need to take a step back and holster our emotions for just a moment to try and refocus our efforts in discussing the topic with some rationality. I call it the madman’s course because, by finding out where we truly stand today and how we got here, it may involve being shot at by everyone. However, if we look at things a little more objectively, we may find out that we’ve helped dig each other’s trenches before we open fired, and the goal is to get people to stop shooting and reevaluate. With that in mind, I hope my thoughts can be read with an open mind and as a thought-provoking dialogue more than any kind of judgmental attack.

A.) SUMMING UP OBERGEFELL V. HODGES

At the core of Obergefell is the dilemma presented by any discussion of tradition: is tradition set in stone, or is it one that evolves as society changes? For the defender of tradition, Justice Kennedy succinctly sums up the position after discussing the history of marriage: “That history [of marriage] is the beginning of these cases. The respondents say it should be the end as well.” Such is an argument for status quo. Meanwhile, on the other side, Kennedy also sums the position up nicely: “Far from seeking to devalue marriage, the petitioners seek it for themselves because of their respect—and need—for its privileges and responsibilities. And their immutable nature dictates that same-sex marriage is their only real path to this profound commitment.” Such is an argument for change of the status quo by including something new to the traditional understanding.

It may go without saying that the discussion revolves around possibly altering the tradition of marriage, but it is important to remember the absolute necessity of knowing what it is that we are seeking to change before we argue about whether or not to change it. So, looking at marriage historically and philosophically is vitally important to frame the discussion.

There is a key difference between marriage in a philosophical sense (what I like to call capital-T “Tradition”) and marriage in a legal sense (what I like to call lowercase-t “tradition”), and it is imperative that we figure out which one we are talking about when we discuss change. Justice Kennedy does, without outright acknowledging it, make a distinction between the two, by stating the revelation through history of the “transcendent importance of marriage.” He then delves into his personal opinion of what that importance entails as a backdrop:

The lifelong union of a man and a woman always has promised nobility and dignity to all persons, without regard to their station in life. Marriage is sacred to those who live by their religions and offers unique fulfillment to those who find meaning in the secular realm. Its dynamic allows two people to find a life that could not be found alone, for a marriage becomes greater than just the two persons. Rising from the most basic human needs, marriage is essential to our most profound hopes and aspirations.

Furthermore, he says that marriage acts by “binding families and societies together,” using examples from two culturally different historical perspectives. First, from Confucius, in stating that marriage lies at the foundation of government, and then in a quote from Cicero, stating “The first bond of society is marriage; next, children; and then the family.”

Unfortunately, the discussion ends there on the philosophical side. Justice Kennedy provides the smallest and most shallow framework possible before diving into the subject at hand. In his writing, a philosophical look into marriage is almost completely glossed over. This is problematic on multiple levels, but more seriously because the subject is so fundamental to human existence. It deserves a lot more attention than it was given. While the language is flowery and the attempt to tie culturally diverse backgrounds together is intriguing, is it adequate in helping to define Traditional marriage?

Kennedy’s treatment of traditional marriage is not much better. Essentially, a paragraph is devoted to examples of times laws and customs around marriage have changed over the years (in contrast with eight paragraphs detailing the recent history of the gay rights movement). While the few references to changes in marriage customs and law are interesting individually, the reason for mentioning these changes is as a rationale that marriage can, and should, continue to change as society does. Changing marriage is good in of itself, because:

These new insights have strengthened, not weakened, the institution of marriage. Indeed, changed understandings of marriage are characteristic of a Nation where new dimensions of freedom become apparent to new generations, often through perspectives that begin in pleas or protests and then are considered in the political sphere and the judicial process.

So, with all of that on the table, how does Kennedy ultimately define marriage using this background? It can be summarized most by his closing paragraph, which reads as follows:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death.

That definition is a good parallel to the celebrations that broke out after the rulings and the slogan that came forth: love wins. Marriage, in the end, is about love. Fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family, but most of all, love. How can one argue that, and isn’t that what Traditional marriage has always been, even if traditions around marriage have changed? Are we changing Traditional marriage at all, and are we merely changing the laws to correct a flaw in our historical thinking in how to treat it?

B.) THE REAL HEART OF MARRIAGE

Even though the sentences are literally right next to each other and there is an attempt to make them sound similar when discussing the philosophical roots of marriage, Kennedy’s take on marriage is actually quite different from the historical sources he quoted. Kennedy, in his comment that marriage acts by “binding families and societies together,” presupposes the existence of family and society while marriage is essentially the glue. It gives rise to a notion that marriage is a societal construct designed to keep itself whole, and I would venture that many today feel that way.

That is not, however, the way marriage is portrayed by Confucius and Cicero. Later in Kennedy’s opinion, he also quotes de Tocqueville, who ironically contradicts the notion that Kennedy presents in succinct fashion:

[Marriage is] the foundation of the family and of society, without which there would be neither civilization nor progress.

For each of them, even from backgrounds that span from China in 500 BC to more modern times, marriage is seen as the foundation of society itself and is the primary human relationship that society builds upon. In fact, marriage is not just the foundation of society, but gives birth to it. Each person quoted succinctly states that marriage is, in fact, needed for society to exist, and is not merely a construct to hold it together.

What is particularly stunning in Kennedy’s opinion is that Judeo-Christian thought, regardless of one’s opinion of it, was instrumental and vastly influential in regards to marriage in the Western world. Yet, it is not even mentioned in Kennedy’s all-too-brief history of marriage as he skipped 2,000 years of thought and discussion that occurred during the time period between Cicero and himself with a brief mention of de Tocqueville in the middle. That is not to say that Judeo-Christian thought needs to be used as a basis for any form of decision, but when exploring it and its influence on the philosophy of marriage, one would see great detail in the implications that are left out in the short statements of Confucius, Cicero, and de Tocqueville.

Let’s work our way backwards from an end point of a society that is already in existence. Human beings are inherently social creatures, and with higher functioning, we group together and establish rules, both written and unwritten, that govern our interaction between one another. In order for society to function, it requires a population of individuals who have been raised and socialized towards the end of maintaining society. That population does not spring forth on its own, nor does it arrive at common societal norms and behaviors through its own devices. That population needs to be birthed and raised by others. And there, in its patently obvious yet blindingly forgotten form, is the implication of those earlier quotes: at the root of society, at its very foundation, is the formation of new human beings to take part in society. Without them, there are no future generations to whom we can pass society and tradition down.

There is, furthermore, biological obviousness that seems to escape modern dialogue as well. Only one relationship can produce offspring to add to society, and every single living person is the fruit of that natural relationship. We are inherently sexual creatures, and not only that, we are complimentary. We have entire systems devoted to the creation of new human beings that need to work together towards that end. Furthermore, humans have an added dimension of not just working towards sexual maturity and biological adulthood, like the animal kingdom, but also emotional and societal maturity. Apart from some longer lived species, human beings spend an inordinate amount of time working towards that holistic maturity (about a quarter of our entire lives, in fact). This requires others for leadership and, coming full circle, to pass down the traditions and norms of the society that new human beings have been birthed into. With our innate desire to know where we have come from, both physically and societally, the most logical and best suited individuals for that task are the ones that brought that person into the world.

This isn’t a new revelation. This is the inherent implication of marriage as a foundation of society and the very substance of where its Tradition arises. It is inherent in the word itself, which finds its roots not only in joining together, but also mating and impregnation. It is found in the language that surrounds marriage, including husband and wife. It is the first human relationship, and the relationship from which society continues to spring forth and to maintain itself. It is not merely a binding together of societal participants. And, beyond that, the reason that so many philosophers from such wide cultures came to that same understanding is because it is imprinted upon us as a part of natural law. To use the definition used by the Catholic Church, which fills much of that 2,000 year gap in Western thought between Cicero and Justice Kennedy:

Marriage is that individual union through which man and woman by their reciprocal rights form one principle of generation. It is effected by their mutual consent to give and accept each other for the purpose of propagating the human race, of educating their offspring, of sharing life in common, of supporting each other in undivided conjugal affection by a lasting union.

That is why marriage is the foundation of society. Society needs people, and the very relationship that is the ideal for bringing those people into society is marriage. It is a natural order, and there is only one human relationship that can be ordered in that way. This very notion is also at the heart of the treatment various philosophers have given it, as noted throughout the dissenting opinions of the court case, and is the basis for many religious views on the subject.

To go back to an earlier statement I made, there is no hatred or malice in stating that and it is not meant to elicit an emotional response. Rather, it is a simple declaration of the order inherent in our very being, one that was seen by Confucius, Cicero, and de Tocqueville. I have not ventured to state anything that falls outside of the natural order is immoral. We, of course, don’t live in a perfect world, and some things do go askew. Children lose parents, couples can struggle with infertility, some parents struggle with being a parent at all or are not capable of properly raising or caring for their own. However, the existence of these things, as tragic as they are and worthy of empathy, do not invalidate the natural law in the same way that a broken rule doesn’t render a rule meaningless. Even in the bleakest of situations we can still orient our actions towards their natural ends.

That is true Traditional marriage, the one which is imprinted upon humanity and which society, throughout history, has tried to promote. However, this is not the basis that has been used in any of our current debates. The situation is, unfortunately, much more complicated than that.

C.) THE SLIPPERY SLOPE PREDATES GAY RIGHTS

Many of the arguments proposed by those who oppose gay marriage center on three main notions: 1.) if the person who opposes gay marriage is religious, they often find that it violates the sanctity of the institution as they believe it to be, 2.) marriage is between a man and a woman, and 3.) gay marriage is a slippery slope towards other forms of relationships that may be morally unacceptable. The trouble is, the Traditional marriage they are trying to defend has actually been changed long ago by the very people trying to defend it.

In terms of the holy nature of marriage in a religious sense, a counter argument often comes up in regards to things like divorce. How holy can an institution be if divorce is acceptable? This is a very valid point, but it actually goes much deeper than that. Here are a few quotes that show this point:

“Lastly, there is matrimony, which all admit was instituted by God, though no one before the time of Gregory regarded it as a sacrament. What man in his sober senses could so regard it? God’s ordinance is good and holy; so also are agriculture, architecture, shoemaking, hair-cutting legitimate ordinances of God, but they are not sacraments.”

“No one indeed can deny that marriage is an external worldly thing, like clothes and food, house and home, subject to worldly authority, as shown by so many imperial laws governing it.”

“Not only is the sacramental character of matrimony without foundation in Scripture; but the very traditions, which claim such sacredness for it, are a mere jest.”

“Marriage may therefore be a figure of Christ and the Church; it is, however, no Divinely instituted sacrament, but the invention of men in the Church, arising from ignorance of the subject.”

The first quote is from John Calvin, the rest are from Martin Luther. We like to think that reducing marriage to a societal or governmental construct is a modern invention, but in reality, a reduction of its religious character and placement in the hands of man truly began within the ranks of the very same people today who wish to now argue that marriage is of a special, holy nature. It is the starting point of the thought that marriage Tradition, at the time, was a misunderstood facsimile of some other religious tenet, was entirely worldly, and was no different from other works such as agriculture and shoemaking. Whereas the Catholic Church viewed and still views marriage as a sacrament, or an outward sign of inward grace instituted by Christ for our sanctification, the Reformation began the path of removing the sacramental nature of marriage and handing it over to the world.

Divorce follows along these same lines as marriage continued its journey from the ecclesiastical courts of the Middle Ages towards modern day. Whereas marriages could not be dissolved without special declarations through the religious side of governance, we have seen more prevalence in divorce rates as they continue to trend towards the civil. Whether it be Henry VIII breaking away from Rome and starting his own church because the Pope would not go along with his divorce or the institution of no fault divorce, recent history is full of examples of the dissolution of the institution of marriage that detracts from any kind of discussion of it as holy. Even though divorce rates have declined recently, there is a strong correlation with the decline of people even getting married in the first place. Marriage is not in a holy state, and people are right to dismiss that argument if they are being asked to hold their own view of marriage up to it.

The true turning point in modern marriage, though, was the widespread acceptance of birth control, particularly of a pharmaceutical nature. Whereas there have been various more natural methods of birth control for longer periods of time, the ease and greater reliability of the pill created a large shift. The Constitutional right to privacy, which came from overturning a law against contraceptive medication and instruments, didn’t become law of the land until 1965 in the Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut. It wasn’t until years after that that the same rules were found to apply to unmarried couples.

Even though the current state of birth control is relatively modern, how have religious institutions treated it? The first Christian denomination to accept it as permissible was the Anglican Communion in the 1930 Lambeth Council. Since then, other Protestant denominations have mostly followed suit, either permitting its usage or staying silent on the matter. The Catholic Church still actively opposes it and is usually lambasted by others in holding onto what is seen as an archaic belief. Several encyclicals, including Pius XI’s Casti Connubii in 1930 and John Paul II’s Humane Vitae in 1968, have been written about the subject during that timeframe.

I bring up birth control and its history not as a moral argument here, but rather to show that we have as a society accepted not just divorce in a physical sense, but we have also philosophically divorced procreation from marriage. It is no longer connected to it at all as a purpose of the institution in the modern mind, but is rather something that can or may happen during a marriage. In fact, modern society doesn’t even associate it with marriage at all, as having children outside of marriage grows in acceptance. Procreation has become a separate choice. The dissenting opinions in the Obergefell case were quick to pick up on this as being the core of the Tradition that is being changed, but no one traces it back to a root cause nor realizes it has already been changed before they put pen to paper. The root cause is that modern birth control options have simply allowed us to separate procreation from marriage, and it has facilitated the transformation of the nature of sex from procreation to recreation.

Kennedy’s decision is riddled with the assumption that procreation is separate from marriage, and he isn’t necessarily wrong in interpreting society’s modern stance in that regard. Discussions of children permeate the document, but never in connection with the relationship that actually brings forth the children. They almost appear as free flowing entities that deserve the dignity of having legally recognized parents, but are wholly disconnected from their own generation through biological ones. However, it reflects that removal of procreation from the marriage discussion, which can be summed up in his passage in regards to it:

An ability, desire, or promise to procreate is not and has not been a prerequisite for a valid marriage in any State. In light of precedent protecting the right of a married couple not to procreate, it cannot be said the Court or the States have conditioned the right to marry on the capacity or commitment to procreate. The constitutional marriage right has many aspects, of which childbearing is only one.

Again, childbearing is something that can spring forth from marriage, but is not a part of its core. They are separate. So separate, in fact, that you have a right to abstain from procreation entirely.

If you have no issue with the separation of procreation from Traditional marriage, but yet still believe marriage is between a man and a woman, then the question is this: why? What special place does the relationship of a man and a woman hold if the natural order of marriage no longer has anything to do with procreation as a part of it? What are you left with, besides sharing life in common and supporting each other? What you are left with is virtually no different than what Kennedy has defined marriage as in his opinion. What we are left with is defining marriage by the other things that are born from it, one of which is love.

In short, the definition of marriage changed decades before the civil rights movement, and modern Christianity is a part of those that did it. And with that definition, the one which removes the nature of the relationship between man and woman from marriage entirely and merely tries to place a moral license on sexual activity, it is an untenable position to then say gay marriage is not acceptable. Gay marriage, in this case, is a mirror for what we have already made marriage. So, when arguing from that position and saying that gay marriage is a slippery slope, one must realize that they are already halfway down the hill.

D.) THE SLIPPERY SLOPE DOESN’T END HERE

Although gay marriage mirrors the concept of marriage that society has already changed, there is truth to the argument that it opens the door to further broadening. Much of the focus has been placed on how “man and woman” is merely traditional, and traditions change. However, with the changing of the traditional sense of that phrase, one must realize there are a number of other implicit traditions that can tumble with the same precedent. And, according to Kennedy, can that not only strengthen marriage further?

It has already been discussed that modern society has entirely removed procreation from the concept of marriage, and therefore it is hard to argue that the distinction of “man and woman” should continue if that is the case. However, if procreation is no longer any part of marriage, incestuous relationships should no longer give anyone pause. Many of the arguments against incestuous relationships center on biological issues via procreation, but how can that be an argument when procreation is no longer in the picture? What if they are two brothers or two sisters anyway?

And what about numbers? Even though “man and woman” has been removed, the implication of marriage being between two people still exists. Can multiple people not love each other, show fidelity, be devoted, sacrifice, or have a family? Isn’t polygamy just a new dimension of freedom that will become apparent to new generations?

If we’ve moved beyond Traditional marriage and are beginning to reshape it using the traditional, let’s look at Kennedy’s four main points for allowing gay marriage:

The right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy.

If personal choice regarding marriage is inherent to individual autonomy, how can we possibly deny anyone their personal choices when marriage is involved, regardless of the number of people or family relation?

The right to marry is fundamental because it supports a two-person union unlike any other in its importance to the committed individuals.

Based upon all of Kennedy’s arguments, and how we are now acknowledging marriages ever-changing nature based upon how society views it, how is a two-person union a valid part of this argument? Nowhere after he mentions two-person does he expound upon it. It is an assumption. And, through his other arguments and explanations, it is an assumption that can no longer hold water.

It safeguards children and families and thus draws meaning from related rights of childrearing, procreation, and education.

After making this statement, Kennedy’s entire argument is based upon childrearing and the dignity that children deserve by having legally recognized parents. Oddly enough, even though the right to procreate is mentioned, it is followed up with the notion that there is a right not to procreate. Kennedy cancels the two out in short order by saying one necessitates the other which, again, already flows from modern society’s take on the matter where procreation is no longer an integral piece of marriage.

This Court’s cases and the Nation’s traditions make clear that marriage is a keystone of our social order.

Kennedy goes on to say how marriage is something society blesses with a constellation of benefits to “protect and nourish the union.” Not allowing access to those benefits, therefore, demeans gay couples and teaches that they are unequal in important respects. Don’t we demean other forms of marriage between adults by blocking them from the same benefits?

Short of continuing to hang onto “two-person” marriage as a vestigial organ of the Traditional marriage, many other kinds of relationships fall under the same criteria Justice Kennedy outlined. Furthermore, they fit into Kennedy’s definition of marriage. There is often a bristling over the implied moral equivalence of certain relationships, but truly, they are a natural logical end to the path we are already treading regardless of anyone’s personal opinion on their morality. And, truly, don’t they fit the modern view? If love wins, then shouldn’t we open the door for all love? If you deny other relationships the same rights, you are no different than those who oppose gay marriage.

E.) WE’RE IN THE TRENCHES TOGETHER

The marriage debate has turned into the quintessential example of Matthew 7:3-5:

Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye? How can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when all the time there is a plank in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.

On the one side, we refuse to acknowledge the changes to Traditional marriage we have already instituted and become complicit with, yet we yell at others who actually mirror what we’ve already changed it into. On the other, we decry the hypocritical views of our opponents, yet refuse to acknowledge the door is now wide open. The truth is, both sides are in the same trench, and that trench is a world where procreation, children, and the continuation of society are no longer at the heart of marriage and how it is ordered.

Hannah Arendt once said “the most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution.” The revolution has occurred, and now Kennedy’s take on tradition reemerges. This history of marriage is now the beginning of future cases. Should it be the end as well? If we are constantly finding new dimensions of freedom, will we eventually find them all and reach the TRUE definition of marriage, or is it always changing, amorphous, and has no definition at all?

To reiterate, I am writing not to preach or enforce a particular morality on those who are reading this. I am endeavoring to refocus the debate, and I’m calling for a larger introspective look at how we treat marriage through recognizing the logical progression of how we got here today. We all need to take a moment and reflect on recent events. It is hard to argue that we are undergoing social change at a rate that has most likely never been seen before. One thing we should reevaluate is our own lives, particularly before we point at others. We need to stop shooting at each other and remove the planks from our own eyes. Reevaluation is important because we, at some point, need to realize that it is other human beings we are shooting at in the trenches, and each human person should be afforded the same dignity regardless of their opinion or of their actions.

I’ve said to friends before, I hope that everyone can agree on one thing: the reason we argue about marriage is because we all feel marriage is important and that it has deep roots in the human soul. Both sides are, in fact, aiming for the same goal of solidifying that importance, albeit from different angles and for different reasons. We all feel it is important because, deep down, we know that marriage gave birth to society and was not created by it.

So, each of us are endeavoring to do that one thing, which is building a foundation on which our future society will rest upon. Let’s all continue to come to an answer together and recognize that the vast majority of people are not arguing from a position of malice, but are instead trying to solidify a society that they feel is ordered towards the good of man, for ourselves and for our future. We simply need to realize that we can never accomplish that without deep reflection, a proper understanding of all sides, and most importantly and regardless of the outcome, a common notion that everyone deserves the dignity of the human person.